(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — Here’s what we humans have in common with oceans, lakes

and rivers: We have solitons coursing through us.

“A soliton is a wave that can propagate for a long time, without changing much,” said

Bjorn Birnir, a professor of mathematics at UC Santa Barbara. The wave was noticed by Scottish

civil engineer and naval architect John Scott Russell in 1834, when a boat in a narrow channel

drawn by horses suddenly stopped, and set in motion a “large solitary elevation, a rounded,

smooth and well-defined heap of water,” which rolled along the channel for miles with form

and speed unchanged until the course of the channel changed.

This form-preserving, energy-efficient solitary waveform, according to a paper by Birnir

and colleagues in Madrid, Spain, is also what drives angiogenesis, the growth of new blood

vessels from existing ones. It’s a process essential to the development of the embryo and the

healing of wounds, as well as the growth of cancerous tumors and their spread. By quantifying

the equation of the process that occurs at the tips of developing veins, Birnir said, it becomes

possible to create control theories that can govern the development of anti-angiogenic drugs,

or conversely, create therapies that hasten the development of blood vessels.

“The soliton has the property of keeping its form,” said Birnir, “and what that means is

the tip of the vein is not changed; it has the same form from the time it begins to grow to the

time it ends. That is the property of the soliton that makes sense in this context,” Birnir

continued, something that deals with unchanging, invariant form.

For their paper “Soliton driven angiogenesis,” published in Nature Scientific Reports,

the researchers took into consideration a recent model of tumor-driven angiogenesis, the

growth of blood vessels in response to growth factors and other chemicals secreted by the

tumor.

“The tumor wants the oxygen that these veins bring because that’s necessary for it to

grow,” Birnir said. Without a regular blood supply, tumors cannot grow beyond a certain size,

nor would they have a route by which to disperse to other parts of the body.

“What we discovered is that the only thing you really have to worry about is how the tip

of the vein grows because if you figure out how the tip grows then you have figured out the

path of the vein, and what the vein would look like,” he explained.

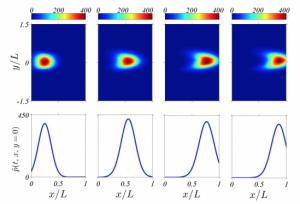

As they studied density plots that represent the growth and movement of vessel tips

marching toward a tumor, the researchers realized that the profile of the lumps that the vessel

tips formed was that of a moving pulse.

This moving pulse looked very familiar to Birnir, who has done extensive work with

solitons. There are different kinds of solitons that occur in a variety of areas, such as fiber

optics, liquid crystals and quantum field theory, each with equations of varying complexity and

solvability.

This particular angiogenesis-driving soliton, it turned out after further analysis and

simulation, was described by the Korteveg-de Vries (KdV) equation, a mathematical model of

the waves that were initially reported by John Scott Russell. Not only did it fit what Birnir calls

“the most famous soliton of all,” in this case it also indicates that all solutions can be mapped

out for the rather complex equation.

“In mathematics this soliton is described by a system that’s called integrable; it’s

something that you can actually write down a solution for,” he said. “It’s a nonlinear solution of

a nonlinear partial differential equation.”

This knowledge is also applicable in other conditions where blood vessel growth is a

factor, such as in the eyes of premature babies, in which case therapies may be developed to

promote the moving pulse of soliton-driven angiogenesis.

“This is why mathematics has to come first and you have to have a mathematical

model,” said Birnir. “Once you have a mathematical model and can compare it with the real

phenomena, if you are convinced that it really describes the real phenomena then you can do a

lot of other things, maybe get a new understanding and think about a new control.”

Research on this project was conducted with Luis Bonilla, Manuel Carretero and Filippo

Terragni at Universidad Carlos III in Madrid.

- Faculty

- The Current

- Solitons

- Biology

Related Link:

October 4, 2016 - 9:06am